April-July

2021

2021

Impression of a Mine

Inst. Leila Tolderlund

“There is life in a stone. Any stone that sits in a field or lies on a beach takes on the memory of that place.

You can feel that stones have witnessed so many things.”

-Andy Goldsworthy

![]()

You can feel that stones have witnessed so many things.”

-Andy Goldsworthy

The Impression

From above, facing NNE

From above, facing NNE

This project reached installation on April 15, 2021.

But its story begins around 105 million years ago, off the coast of the Cretaceous Sea, which once split North America from the Artic to the Gulf of Mexico.

But its story begins around 105 million years ago, off the coast of the Cretaceous Sea, which once split North America from the Artic to the Gulf of Mexico.

Currents deposit sediment as layers of shale, clay, and sandstone - the Dakota Formation.

The foothills of the uplifting Rocky Mountains are beaches.

Great lizards step through wet sand, leaving impressions which last.

The foothills of the uplifting Rocky Mountains are beaches.

Great lizards step through wet sand, leaving impressions which last.

Front: Eolambia Tracks at Dinosaur Ridge; Wikimedia Commons

Behind: North America Geographical Map; USGS

Behind: North America Geographical Map; USGS

The ground uplifts. Seas change to rivers. People come along!

For millenia, many indigenous groups live along the front range of the Rockies.

Among them are the Arapaho (Hinono'eino), Southern Cheyenne (Tséstho’e), and Lakota (Thítȟuŋwaŋ).

Front: Arapaho Camp c. 1870; National Humanities Center

Above-Left:

A train departs Silica for Denver; Douglas County Archives

Below-Left: Clay mining trenches and pits; Golden Today

Right: Stamped Silica Brick; Roxborough Area Historical Society

Below-Left: Clay mining trenches and pits; Golden Today

Right: Stamped Silica Brick; Roxborough Area Historical Society

New people arrive, with incentive to extract.

Ancient seabed can be mined, crushed, and mixed.

South of expanding Denver, the Silicated Brick Company is incorporated, producing bright-white masonry.

Ancient seabed can be mined, crushed, and mixed.

South of expanding Denver, the Silicated Brick Company is incorporated, producing bright-white masonry.

Demand dries up, and the business takes a turn.

One afternoon, the kiln goes cold and is never relit.

The last engine on the branch line is the one that unmakes it.

Above-Right: Colorado & Southern Engine #69; John W. Maxwell

Below-Right: View along former Silica line, SE at Highline Canal Trailhead; Google Maps

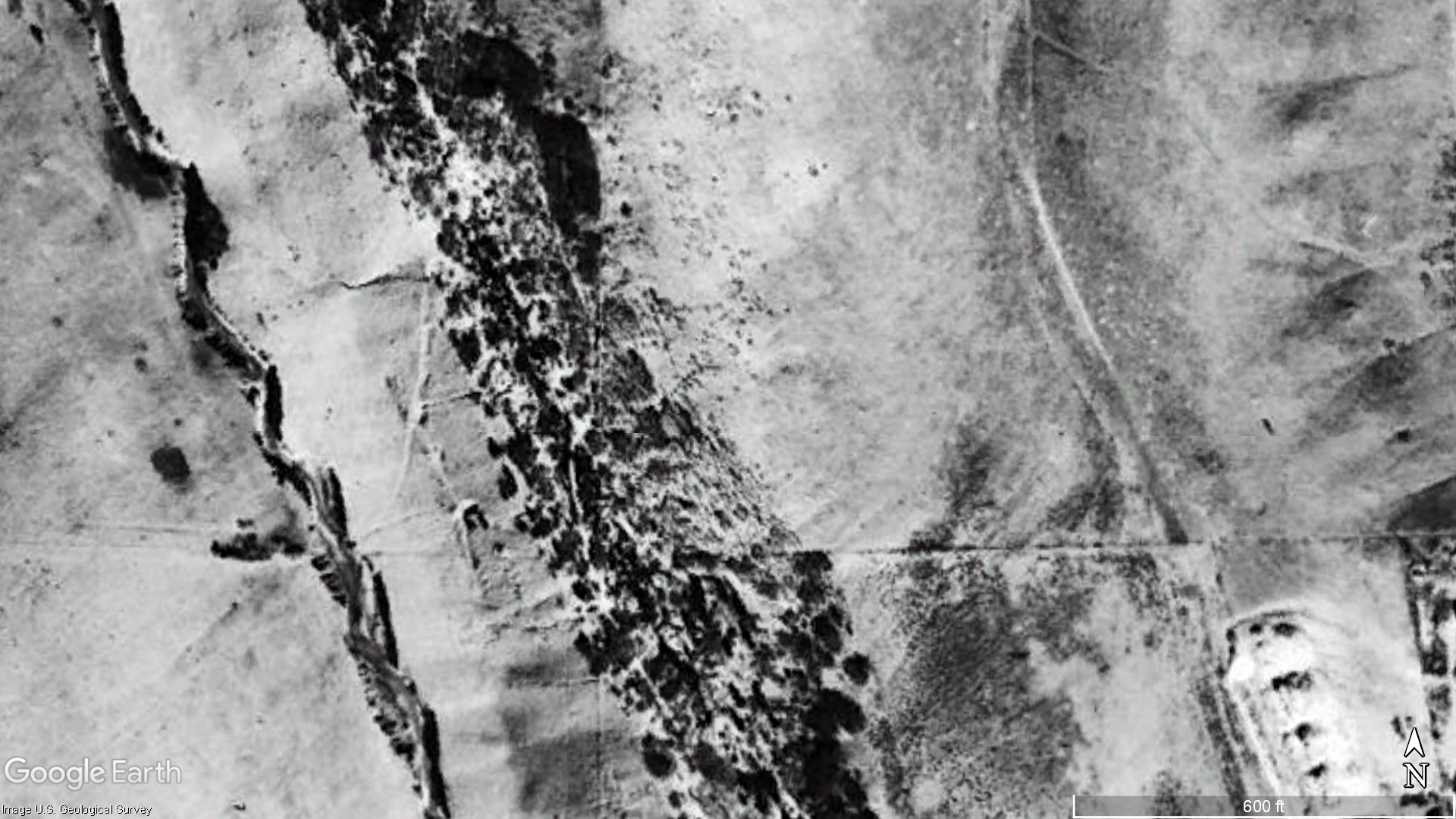

Across generations, and in all seasons, the hill wears its scars.

Mine shafts are imperfect, distinct, dangerous memorials to the origins of a community.

Until, one day, they are no more.

For decades, the mines are left opened, eventually blocked off only by rusted barbed wire.

In July 2017, a middle schooler falls 115 feet down a shaft - and survives.

Some time between then and May 2018, the mines are unceremoniously graded over.

Above-Left: West Metro FD pulls the 13-year old from a mine shaft; KKTV

Below-Left: The hogback mines graded flat

Right: The mines in June 2017 and May 2018; Google Maps

This installation was an attempt to create an impression of the now-gone mine shafts;

An attempt to use simple geometry to acknowledge and channel the memory of the stones;

An attempt to feel once again the scale of a huge hole cut into the ground;

An attempt to impose another form upon the imposable earth, but with more intentional impermanence than the original mines.

These photos were taken over almost exactly two months, as Colorado’s spring breathed its final cold sighs and gave way to summer. 5 weeks in, a new addition appeared, placed right in the center of the impression. Whatever the intention or interpretation of my anonymous co-creator, it gave me great joy to see.